Discounted Cash Flow when calculating Intrinsic Value

- Kylan Ross

- Jun 12, 2025

- 5 min read

Over the years, there has been great debate as to how to value a business properly. After studying all these different valuation processes, I have found some more helpful than others. The dos and don'ts of valuation are going to be most beneficial to you with conservatism. For the enterprise investor, the very concentration of your portfolio and the low-risk attributes of your investment are what count. As we engage with the markets around us, we realize how few great businesses there are. By definition, a great company is very well hedged against the vicissitudes of the market. With that in mind, we need to be wary of not paying too much for them in the short term. So, how do we start valuing a business, and what’s the best way? My opinion will come as zero shock to anyone. Buffett remains supreme in his evaluation approach.

Buffett uses what’s called the DCF approach (Discounted Cash Flows). Buffett’s mentor, Benjamin Graham, in the 1930s-1950s, emphasized looking at earnings per share (EPS), book value (assets – liabilities), and coined the “net-nets” (those selling for less than their net current assets). Not that there is anything wrong with this way of doing it, the markets have gotten someone technical, and amongst big corporations, a lot of accounting principles have been dressed up for these types of metrics. Buffett, having noticed this really evolved Graham’s approach. Free cash flow didn’t evolve until the 1970s-1980s, and we’re glad for this because it’s the most accurate number when finding true owner earnings, meaning the long-term cash generating power of the business, as well as cash that is available to shareholders. Let’s begin with step one.

Step 1 – Estimate Future Cash Flows by looking at historical cash flows.

We want to pull up at least the last ten years of cash flows. We’re looking at “free cash flows.” You get free cash flows by taking the operating cash flow and subtracting that from the capex. After getting the averages of the previous ten years of the free cash flows, we can begin to build out what that would look like in the future. For our example, let's build out just five years.

Year | Free Cash Flow |

1 | $100 |

2 | $110 |

3 | $120 |

4 | $130 |

5 | $140 |

This gives us a basic estimate of what the company will produce in free cash flow.

Step 2 – Applying a Discount Rate

This is the rate of return you require to invest in the business. Often, we call this the “cost of capital” or your desired return. Let’s be conservative and assume we would want a 10% annual return. For point of reference: Low-risk, very stable companies like Coca-Cola, Procter & Gamble, we would use a discount rate between 7-9%. For average companies, we would use 8-10%, and for high-growth companies that have more risk, we would use 11-15% or more.

Step 3 – Discount each year’s cash flow to present value

Here’s our Equation:

PV = FCF / (1+r) n

Year | FCF | PV @ 10% Discount Rate |

1 | 100 | 100/(1.10)^1 = $90.91 |

2 | 110 | 110/(1.10)^2 = $90.91 |

3 | 120 | 120/(1.10)^3 = $90.16 |

4 | 130 | 130/(1.10)^4 = $88.74 |

5 | 140 | 140/(1.10)^5 = $86.94 |

Once we add those together, we get $447.66. Let’s pretend this is in millions – so $447.66 million.

Step 4 – Add a Terminal Value

Here’s our updated Equation:

TV = FCFfinal X (1 + g) / (r – g)

The long-term growth rate (g) assumes the company will continue to grow at a steady rate. It is at 3% because we are taking into account long-term inflation or GDP growth. 3% is commonly used due to the long-term level of inflation on a per annum basis. This makes it a conservative and sustainable assumption. This formula estimates the present value of all future cash flows beyond year five, assuming they grow at a steady 3% rate per year. Many intelligent investors cap ‘g’ between 2-4% for conservative measures. The danger would lie if we set ‘g’ too high, and we can produce unrealistic values and bigger overvaluations. So why does the growth rate match inflation when figuring out the cash flow growth? We are assuming that the business will keep growing in value, earnings, and cash flow year after year, forever at a modest rate. The modest growth is benchmarked against inflation. Inflation measures the rise in costs and wages over time – if the business keeps up with inflation, its real purchasing power stays constant. Meaning, if a company’s revenues and costs rise equally with inflation, its free cash flow grows in nominal terms (total dollars) at roughly the inflation rate.

Back to our Equation:

TV = 140 X 1.03 / 0.10 – 0.03 = 144.2 / 0.07 = $2,060 million

Now, we discount the terminal value to today:

PVTV = 2,060 million / (1.10)5 = 2.060 / 1.61051 = 1,279 million

*Note – PVTV stands for “present value of the terminal value.”

Because the value occurs in the future, we need to discount it back to today – that’s why we calculate the ‘present value of the terminal value.’

Step 5 – Add it all together

Intrinsic Value = PV(years 1-5) + PVTV = 447.66 million + $1,279 million = $1,726.66 million

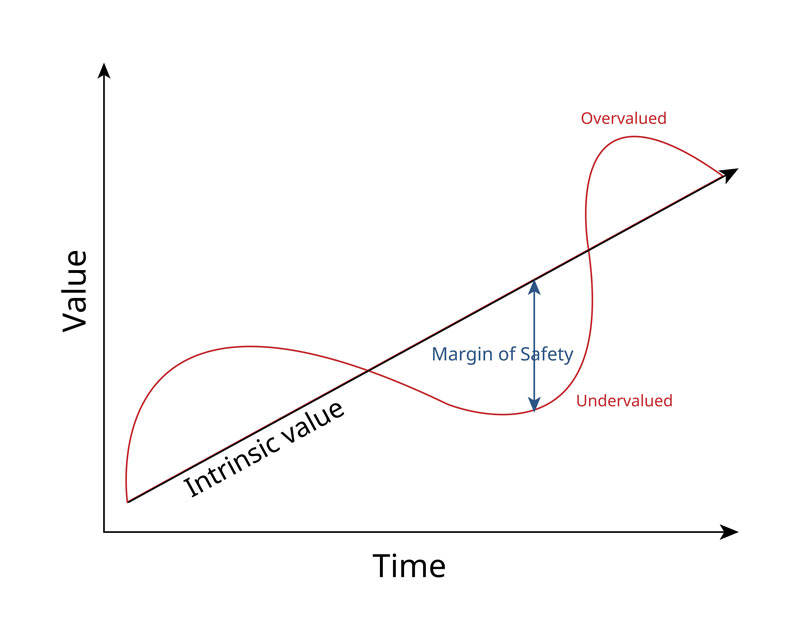

At last, we will find whether or not the company is a good deal or not. Keep in mind that calculating intrinsic value is one of the many things on the checklist list so it isn’t the end-all be-all, rather a key tool to figuring out if there is a disparity in price and value. If the company’s current market cap is $1,200 million, it may be undervalued. If the market cap is $2,000 million, it's overvalued relative to your required return and assumptions. However, we are not yet finished. We need to consider the company's debts. We should look at the company’s balance sheets to take a peek at the total debts (total debt = short-term debt + long-term debt) and cash equivalents.

Okay, so we landed at 1,7 million being our number. Say our total debt equates to 30 million, and our cash equivalents are 10 million. It would look like this:

Our Intrinsic Value: $1,7 million (1.7 billion)

Total Debt: $30 million

Cash: $10 million

We would take the $30 million in debt and subtract it from the company’s $10 million cash equivalents, and get $20 million left over. It would look like this:

$30 million (debt) - $10 million (cash) = $20 million

1,7 million - $20 million = $1,5 million

So, if the company has 1 billion shares outstanding, we would divide 1.5 billion / 1 billion, and that gets us our per share value of $15.

Step 6 – Margin of Safety as the Final Guardrail

Even with a good valuation, we need to have a built-in buffer. If you believe the intrinsic value of the company is at 1.5 billion, you may consider buying only if the stock is trading at an additional 15-30% discount below that number. If we took a 15% discount, that would be considered a purchase price at a market cap of 1.27 billion. The margin of safety is such an integral part of value investing because we can’t predict the state of the economy or the market. Whenever we are purchasing parts of a business through stocks, we need to have this built-in safety net. Going back to the true meaning of investment from Benjamin Graham, “An investment operation is one which, upon thorough analysis, promises safety of principal and an adequate return. Operations not meeting these requirements are speculative.”

Life is rich,

Kylan

Comments