History of the Markets

- Kylan Ross

- May 1, 2025

- 4 min read

In one of Berkshire Hathaway's annual meetings, a question was proposed to Warren Buffett on what he thinks colleges and universities should teach on investing. His response was peculiar, as he said most of what is taught is "pure nonsense," talking about modern portfolio theory amongst other ideas/theories. Buffett says that he would have two courses, one of which would be on how to value a business and the other on how to think about markets. Today, we focus on 'how to think about markets.'

In the 1820s, the railroad industry was considered a tech boom, much of which is compared to the late 1990s and early 2000s. Railroads were a transformative technology that revolutionized transportation and commerce at the time. Investors stemming from Britain and the US brought money in droves to railroad ventures with all kinds of high expectations, hoping and praying for profit. From the 1820s to the 1850s, thousands of railway companies were launched between Britain and the US. Investors at that time had speculated and were encouraged by overoptimism on returns on capital and massive profits; the marketing was everywhere. Shares were often sold before tracks were planned or laid due to the hype alone of this technology. Railroads were overbuilt, poorly managed, and lacked infrastructure. Naturally, the panic of 1857 was a direct result of the overleveraged railroads being funded through easy credit. Stock prices collapsed, and dozens of railroads went bankrupt. The lesson here remains somewhat the same with how we view markets: don't speculate. The lack of due diligence, overleverage (debt), and blind optimism with future growth were fatal to investors.

The 1920s had looked a bit different. Known as the 'roaring 20s,' the entire decade was covered with economic growth and social change. Music, fashion, and stock peaks unheard of. Stocks in companies more than quadrupled in value during this time period of bull market euphoria. As investor confidence was rising and companies were having Mount Everest level evaluations, many investors and corporations borrowed more money to enter the markets as optimism was excessive. Prices for stocks had detached from fundamentals: buying on margin, easy credit, and a belief in a new era of prosperity in America. As you can see, this story is starting to unfold. The 1929 stock market crash is recorded in history as a major reference point in the markets and what had carried over to the Great Depression.

1929-1932 were the damnest of times for America. On October 4th, 1929, what is known as Black Thursday had 12.9 million shares traded. Over the four-year stint of the Depression, the markets had lost 90% of their total value. An even wider impact had happened, with over 9,000 banks failing (due to overleverage) and unemployment reaching 25%. Benjamin Graham in the Intelligent Investor wrote, "During the depression years, it was not the soundness of the security that mattered, but whether the public was in a mood to buy anything at all."

During WWII, the markets remained surprisingly resilient. Markets were cautious and declining from 1939 to 1941 due to uncertainty and fear. However, from 1942 to 1945, the market returned over 100%, meaning price appreciation and dividends were more than double what you started with.

The 1980s and 1990s were years of steady growth in America and a bull market where dreams were made. The average annual return of the S&P 500 during these two decades was 18%—one of the greatest bull markets in history. That takes us to the 'dot-com' bubble burst of 2000-2002. With technology stocks booming in the late 90s, this led to massive overvaluation of internet companies, most with low profits. Most of the dot-com stocks lacked intrinsic value (a concept we broke down last week), reflecting optimism and not fundamentals of valuation. In other words, hype. Benjamin Graham puts it in this way: "The investor's chief problem - and even his worst enemy - is likely to be himself." This led to the NASDAQ falling over 78% during this period. Between March 2000 and October 2002, the markets lost over $7.4 trillion.

In recent memory, many people know the pain they felt during the 07'-08' financial crisis. The background actually sets this up pretty well. From 2002 to 2006, the housing bubbles in America were surging due to low interest rates and mortgage-backed securities. The belief was that housing prices, stocks, and assets never go down. Oh boy, does history repeat itself! During this period people took on too much debt to purchase homes and other assets, and Wall Street investors piled into REITs (Real Estate Investment Trusts), and other mortgage-related industries all while not having an understanding for the inherent risk. In November 2007, the mortgage defaults began rising. In 2008, Bear Stearns collapses and is bought by JP Morgan for $2 per share. Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy, which is the biggest US bankruptcy in recorded history, and the global markets crashed. The US saw extreme volatility - seeing daily swings anywhere from 5-10% became a normal occurrence. The S&P fell from 1,565 (October 07') to 676 (March 2009), wiping out 57% of the market.

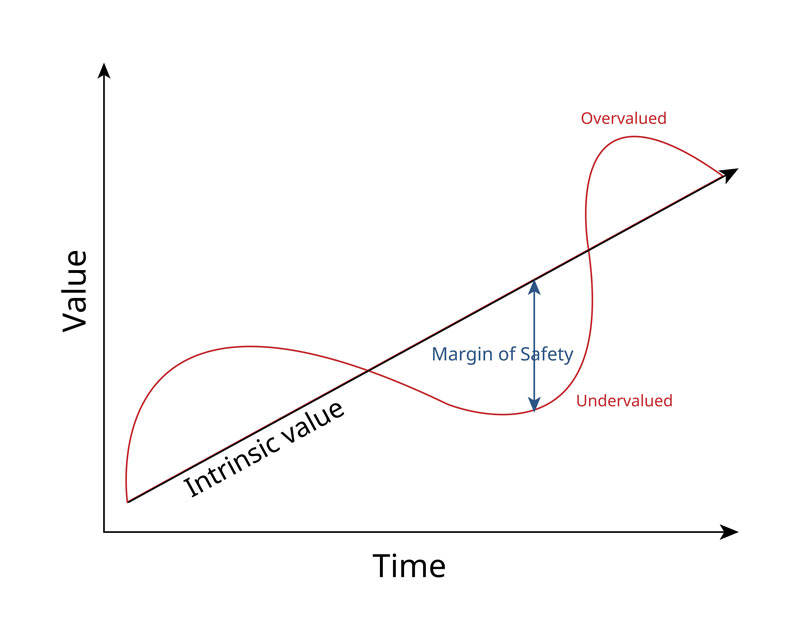

When we look at history over the past 100 years, we see some financial developments that have arisen, been corrected, crashed, and ballooned up. Understanding the history of the markets is something that is important to understand and know what kind of market we are currently in. As Winston Churchill said, "Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it." This ties directly into how to think about markets. In life, in order to go forward, we often need to look back. Looking at various periods of time and watching market behavior, consumer behavior, and speculation can teach us a lot about what not to do. I think in life a guiding principle isn't necessarily figuring out exactly what you should do but rather what is most avoidable. When gauging markets, the same rules should apply to the intelligent investor: don't confuse price with value, avoid leverage, do your own analysis, buy when others panic, sell when it makes sense and when others get enthused (ideally you want to hold forever), and invest with a margin of safety. Next week we take on the economics of COVID-19 and the markets leading up to today.

Life is rich,

Kylan

Comments