Mr. Market's Euphoria

- Kylan Ross

- May 22, 2025

- 4 min read

Mr. Market can tend to be more delusional than rational. This week, we continue our segment on how to think about markets like an intelligent investor. Earlier this week, I was commuting to and from different meetings and ran across a podcast that struck me as gold. A man by the name Mohnish Pabrai was speaking on behalf of value investing and shared some thoughts I thought were truly inspiring. First, was that the idea of value investing is to turn down 99% of opportunities that present themselves to you. Why is that the case? True value investors are seeking deep simplicity. Monish describes these opportunities as 'looking for things that hit you in the head with a 2X4.’ The opportunity has so much meat on the bone, where the math just doesn’t make sense. It’s so unbelievably obvious that Mr. Market has it priced incorrectly and that you are going to make good returns on the investment. These types of investments typically are found at the crossroads of high uncertainty and low risk.

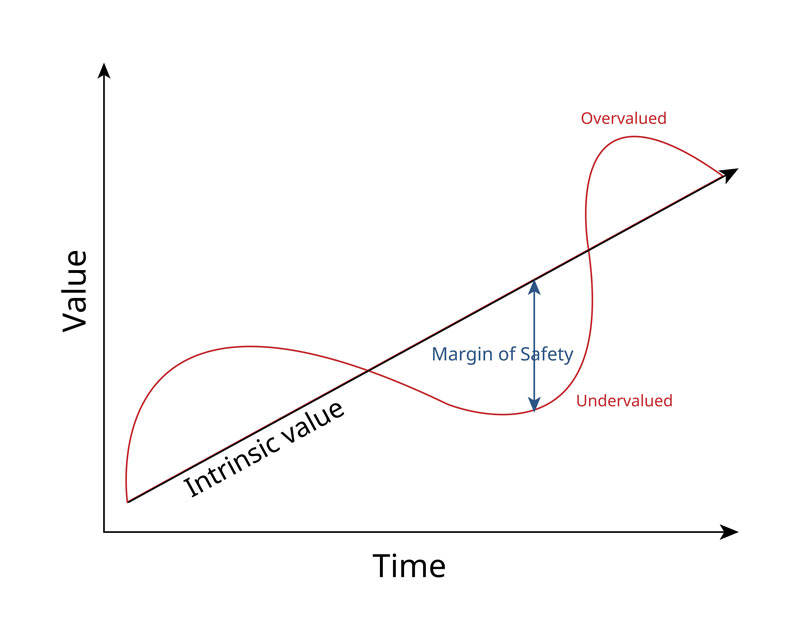

As intelligent investors, we don’t see the market as a source of truth; we see it as a tool. As Benjamin Graham would say, “It’s a voting machine in the short term, but a weighing machine in the long term.” Remember that stock price movements don’t communicate to the public what a stock is worth; it just tells you what someone is willing to pay for it today, because Mr. Market doesn’t care if it’s rational or not. The intelligent investor seeks value by thinking of stocks as ownership of a business. Price is what you pay, value is what you get. We don’t need to predict the next month, quarter, or even the next year. If we understand the business, financial statements, and the price gives us a margin of safety, we can act accordingly. This protects the investor against risks too incidentally (more on this a little later).

Markets are driven by optimism and cast down with pessimism. Securities indeed tend to be overvalued, especially in this modern era we are in. A commonality amongst all types of investors is that investors are naturally future-oriented, and markets often price in future growth. What this means is that prices frequently overshoot the intrinsic value of companies and engage in speculative behavior. Over the long run, stock markets tend to go up, not because every stock becomes more valuable, but because capital chases returns. Within the market, there are endless supplies of liquidity, rising and falling interest rates, and growth narratives. This tends to create a general overvaluation, especially for high-growth popular sectors.

In recent history, the rise of index investing and ETFs (Exchange-traded funds) has automatically poured money into the largest stocks, keeping true evaluation of companies out of the picture. Think of the 'Magnificent Seven’ in this group. Not only indexes but retail investors have come out of the woodwork in recent years due to new technologies like Robinhood and mobile financial service companies – this naturally leads to more investors chasing narratives and stories instead of fundamentals. Third, Wall Street incentives prioritize quarterly performance instead of long-term performance. This is because all public companies are required to report earnings every quarter. CEOs and other C-Suite Executives are focused on meeting earnings estimates and putting those numbers before the board, and then soon after before the shareholders. Missing quarterly guidance by even a few cents can lead to selloffs, despite the long-term fundamentals of the company remaining intact. Wall Street and its analysts react often sharply to these reports and reallocate capital based on this short-term news. Turns out, only 48% of forecasts are correct. Between 2002-2021 found that those analysts who gauged the different price targets from the stock market index at the beginning of the year until the end of the year had an 8.3% success rate ("The Terrible Track Record of Wall Street Forecasts"). I’m not sure if you know, but this is a failing grade.

To counter this argument, not all stocks and companies are overvalued. This is where value investors show up. While the overarching market and certain sectors may be expensive, there are always undervalued securities somewhere. Undervalued securities can exist for a multitude of different reasons. Maybe the company, for whatever reason, portrays to the public uncertainty through earning goals being missed, lawsuits, or other regulatory issues. Cyclical declines happen for certain sectors all the time, leaving “boring” businesses ignored. There’s a psychological explanation behind chasing after what’s sexy and new. Nowadays, we see that with tech and AI. Benjamin Graham would call this ‘market misjudgment,’ leaving the intelligent investor opportunities to look objectively at fundamentals rather than what the overall market is doing.

It can be easy for markets to get ahead and get too optimistic. In a day and age where markets tend to be overvalued, we need to come back to what Mohnish Pabrai says to look to the companies that are currently ‘unloved.’ These are the companies that have very low risk and high uncertainty. The Ying and Yang of exceptional market returns can be hard to find in bull markets like we have seen in the last five years. But we need to ask ourselves, Is there a disparity between companies whose stock prices don’t reflect their long-term earnings power? Is the investing public ignoring unsexy, durable businesses? Has uncertainty pushed back on the price below the intrinsic value? As Buffett says, “If you can learn to be pessimistic when others are optimistic and greedy when others are pessimistic, the better off you will be.” The happy medium remains at the crossroads of uncertainty and low risk.

Life is rich,

Kylan

Works Cited:

Daner , Marc . “The Terrible Track Record of Wall Street Forecasts.” Www.danerwealth.com, www.danerwealth.com/blog/the-terrible-track-record-of-wall-street-forecasts.

Comments